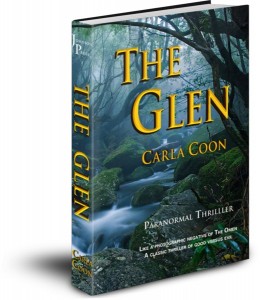

Mark Twain once said, “When angry count to four; when very angry, swear.” A part of me seconds that, another side of me is trying to find other ways to handle anger and frustration. This past week or so, I have been trying to find other ways to handle it in my novel as well. My daughter, who is a nun in Ann Arbor, MI, chastised me right out of the box when she began to read The Glen. In the prologue, three teens find the protaganist outside a gym passed out on the (frickin’ and I wrote frickin) sidewalk. One of the teens says, “Well, help her up, dumba**.” Pretty mild stuff as teens go really, but my daughter called it vulgar and told me that as long as my book had profanity, it could not claim a spot on the convent library shelf.

Mark Twain once said, “When angry count to four; when very angry, swear.” A part of me seconds that, another side of me is trying to find other ways to handle anger and frustration. This past week or so, I have been trying to find other ways to handle it in my novel as well. My daughter, who is a nun in Ann Arbor, MI, chastised me right out of the box when she began to read The Glen. In the prologue, three teens find the protaganist outside a gym passed out on the (frickin’ and I wrote frickin) sidewalk. One of the teens says, “Well, help her up, dumba**.” Pretty mild stuff as teens go really, but my daughter called it vulgar and told me that as long as my book had profanity, it could not claim a spot on the convent library shelf.

Now I admit, when I wrote The Glen, a horror story, the last place I envisioned it was a convent shelf. Still, it hurt to think a few mild swear words would be a death sentence for it there. In my heart, I really felt as if some (very limited and mild) swearing was absolutely necessary to paint a fuller picture of certain characters or to express the urgency, desperation, surprise, or anger during other scenes–never gratuitous, never taking God’s name in vain, and only when it absolutley made sense. I googled, curious what other authors thought. What I found was a good amount of heated debate on the topic, especially in Christian fiction.

The arguments for and against pretty much mirrored the letters passing between my daughter and myself. She spoke of it being unnecessary, sinful, uncreative, offenive to most people and how it reaches for the lowest common denominator (something I taught her and her siblings– ouch!) I wrote to her of realistic characters and dialogue, of painting a picture capable of drawing readers into the story. Our letters were long and filled with examples and strong reasoning. It felt very important to me to make my daughter understand my thinking. It killed me to think she may think less of me or that I had caved on my standards and was merely trying to relate to a secular world.

I have always known that I wrote The Glen for the secular world. I never had any intention of preaching to the choir. To that argument, my beautiful daughter pointed out that purity and decency are actually very appealing to sinners, rather than as she put it, “Here sinners, have some more sin.” I don’t really think that’s valid in the case of the bad behavior of fictitional characters. I expect a gang member, for instance, to swear (even liberally, although only a taste is needed to portray that in dialogue.) I expect it, therefore, it is not shocking. His use of cuss words does not influence me to swear—quite the opposite as his murderous thieving side is also not influencing me to take a life or to steal, but in fact, he is held up as the low-life he is, and all these bad behaviors are seen in this light.

For me, it was coming down to the realism – some people swear, and some people swear a lot. How could I neglect to show at least a glimpse of that in my book? I absolutely refused to compromise my character’s believability, and “Frankly my dear, I don’t give a darn,” just doesn’t work. It’s the difference between a grade B movie and a classic.

For me, it was coming down to the realism – some people swear, and some people swear a lot. How could I neglect to show at least a glimpse of that in my book? I absolutely refused to compromise my character’s believability, and “Frankly my dear, I don’t give a darn,” just doesn’t work. It’s the difference between a grade B movie and a classic.

I once read that a swear word in print is ten times louder than one spoken. I believe that, and I kept that very much in mind as I wrote The Glen. Still after writing up one side and down the other to defend my very light and limited use of profanity, I sent my last letter, and only then did I open my published manuscript to have a look. As I looked at each usage, it was through different eyes and with a certain grace obtained, no doubt, through my daughter’s prayers. I was surprised how easily I could change many of them, how some I could altogether remove, and even a few where I added tiny narration actually improving the scene.

“Let us argue the point” as Mr. Midshipman Easy would say. I did, and my eyes were opened.

I realize with blushing shame that swear words do not hold the same shock value for me as they ought. Get me mad, and I swear like sailor. That is why I had a more difficult time understanding arguments against it in fiction. I came across an article by Bradley Robb, where he explained, “Profanity in its many forms is an assault on the reader and what they hold as dear, a form of mental shock that when used correctly, can jolt the reader….The use of these words has the same effect as the Vandals, dirty barbarians, riding into the white marbled Rome. They desecrate. They destroy. They tear down what we hold dear, they become what we fear.” Later in the article Robb says that, “The pure fact is that sometimes a piece of art has a critical moment when it is necessary to sack the white marble temples of Rome. In others, there are ways to show desecration sans exacting details.”

Sacking Rome should be a rare and careful choice. Afterall, how often does a writer want to assault his readers? However, I believe every writer needs that uncensored autonomy to examine scene by scene, character by character, and line by line whether and where he might judiciously draw his sword for a shocking assault. For some, it will be never, for most, I hope, it is rare, and there will always be those that assault a reader so often the shock is nullified, the effect lost, and the entire work spoiled. Readers too have the same autonomy, free to retreat from future assaults in closing a book.

Well Sister,  my dear daughter, for me the verdict is in, and it makes sense to me now. I promise to do better, to be more careful, more vigilant and judicious with the power entrusted to me in weilding the written word; I swear. 😉

my dear daughter, for me the verdict is in, and it makes sense to me now. I promise to do better, to be more careful, more vigilant and judicious with the power entrusted to me in weilding the written word; I swear. 😉

Thank you for this post! It’s a very good explanation of why too much swearing can be detrimental to a story. I’ll be saving it to share with copy editing customers who need it, because you explained it much better than I could, and you’re coming from their point of view, too! 🙂

Thanks Susan. I was on a learning curve myself over it all – still am.